A Pashmina Primer

- Shila Desai

- Aug 23, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 25, 2023

Do you know your pashmina from cashmere? Or for that matter, if it’s real pashmina?

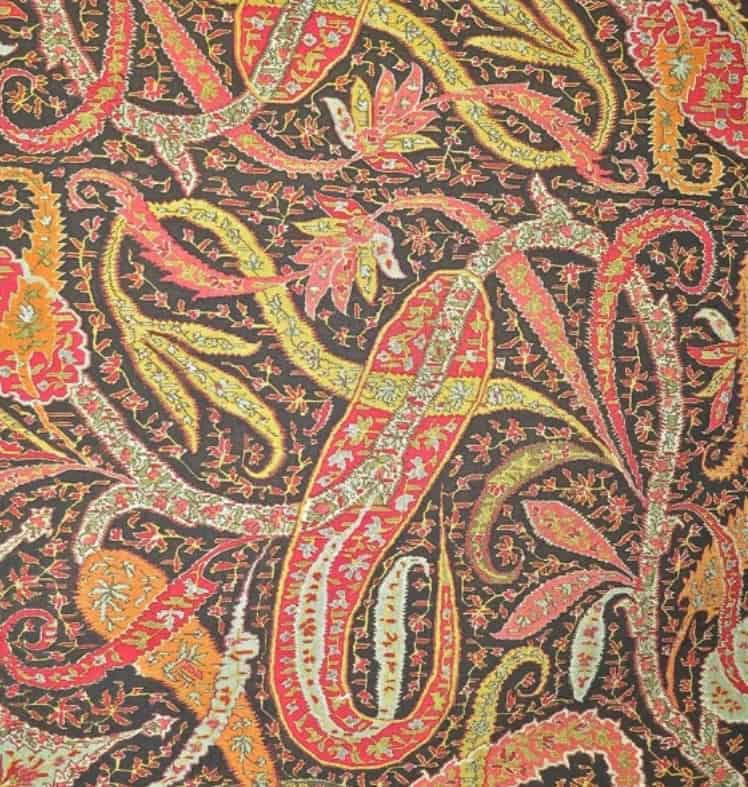

Already endowed with great natural beauty, Kashmir has mesmerised the world for centuries with its pashmina textile tradition. Whether the fiendishly complex Kani shawls or those embroidered with Amlikar needlework, Kashmir’s weavers and embroiderers are in a class of their own. But where does the raw material, pashmina, come from? Unravel a pashmina shawl—if you can bear to—and the trail will lead you to Ladakh.

First, a bit of history.

While earliest records of tapestry designs exist from 7th CE, it was during the 16th CE Mughal period that the Kashmiri shawls rose to the forefront on the subcontinent. Primarily worn by kings and courtiers, the work of Kashmiri weavers found its way beyond South Asia in mid 1800’s to France and then to the rest of Europe. With the advent of the industrial age in late 18th CE came global acknowledgement to this ancient art-form. Kashmir was credited with the artisanship, and it was assumed the raw material too.

It is believed that Napoleon was so impressed that he used pashmina to woo Josephine.

Pashmina

The word ‘pashmina’ derives from the Persian word ‘pashm’, meaning the finest wool fibre. Pashmina is the lightest, warmest and softest natural fabric, and it is made from the finest wool from the underbelly of the Hircus Capra or Changthangi mountain goat which lives in the Himalayas around 14,000 feet above sea level. These goats can survive sub-zero temperatures because of their extra layer of hair which insulates them from the extreme cold. For millennia, Ladakhi peoples have kept warm with fabrics they wove or felted from this fine goat hair. The art of making pashmina probably dates from as early as 3,000 BC with the skill passed down from generation to generation. The Hircus Capra goat produces only between 3 to 8 ounces of pashmina wool in a year, and this wool is incredibly fine, being less than 15 to 19 microns in thickness, whereas human hair is around 75 microns thick.

Cashmere, often confused with pashmina, is up to 21 microns. Technically NOT pashmina. Pashmina is crafted from cashmere.

Cashmere was a term coined by Europeans who couldn't pronounce Kashmir properly. Cashmere is an anglicization of the word Kashmir and originally defined the soft and fine wool acquired from Ladakh, which, in those times was banded for administrative purposes with Kashmir. Due to its climatic conditions, the finest cashmere comes from Ladakh. Whereas Mongolia and Nepal lay claim to “pashmina” production, going by micron thickness the goat hair from these lower altitudes is technically not pashmina—it is cashmere.

As summer in Ladakh approaches, goats’ shed wool is collected by semi nomadic peoples of Ladakh. It is washed, combed, carded, and packed into tufts for selling. At this point, it is of mixed thickness and therefore technically cashmere. The tufts of cashmere wool leave Ladakh to reach the valley of Kashmir. Here, the cashmere is cleaned, soaked, and dried in the sunlight to get dirt and grime out.

The cashmere wool is then taken to households where women diligently spin the wool to fine yarn on the wheel of wool called yinder. The spun yarn is collected around the spindles for further processing by simple homemade instruments. A wooden stick with a round upper portion called thanchorr is used in the process of whirling around the spun fibres. This process is called pranch. The cashmere yarn produced is 12 to 16 microns at this point. Another round of hand-picking over and the finest wool goes into the pashmina pile. The rest is used for cashmere items.

The precious pashmina is now ready for the karkhanas or weavers’ studios.

We will watch this entire process from Ladakh to Srinagar on our upcoming April 2024 tour.

Real or fake?

Basically, the most important distinguishing feature of pashmina is that due to the fineness of the fibre, it can only be hand spun and handwoven. The brute force of power looms will break the fibre. This basic feature is constantly under change. International competition and ever-growing demand for “pashmina” make it tempting to switch to powerlooms.

“Powerlooms can produce 15 shawls per day while a handloom can barely produce two shawls per day,” said Izhan Ahmad, a manufacturer of Pashmina shawls in the Kashmir valley.

A counter argument fears the move to powerloom has compromised the quality of ‘real pashmina’. Powerlooms have displaced many artisans who currently demand a ban on the use of power looms.

Why have powerlooms compromised the quality of real Pashmina?

As a spinner or weaver works, she or he keeps vigil to check for flaws. An attendant on a powerloom tending to up to thirty clacking machines simply cannot match this level of care.

Ayesha, an elderly decades-long pashmina connoisseur, says, “We used to pass real pashmina from one generation to another. But today if you use a pashmina shawl several times, it begins pilling and the durability is no more.”

There are scientific reasons for this drop in quality. Remember that pashmina fibre that cannot withstand the brute force of a powerloom? To strengthen it for the powerloom, nylon and synthetic fibres like viscose, or even silk, are added during the spinning process.

This is where the adulteration happens, where ‘real pashmina’ is spun into fake pashmina.

Powerloom advocates argue that once the fabric is prepared, it is washed with certain acids, which melt away the nylon. They claim that it returns to 100% pashmina again.

But experts disagree. Pashmina loses its quality after the acidic washing.

“It’s like the first copy of something which we buy from the market, almost like the real one. It looks the same, almost feels the same. We are not able to differentiate between the two,” said Izhan. “But over time, true pashmina will retain its sheen, warmth, and lightness for generations.”

Tests to determine real or fake pashmina

Genuine pashmina is not perfect.

Pashmina is 100% handcrafted, right from the spinning of the wool to the fine embroidery on a woven scarf or shawl. There should be slight irregularities in the weave or colour. A machine woven cloth will be completely even and perfect, as will any embroidery work.

Pashmina does not create static electricity

There should be absolutely no static electricity if you rub two sides of a pashmina together. Synthetic fibres like polyester and acrylic create static electricity.

The ends of a pashmina are unfinished

The two ends of a pashmina (the short sides) are always unfinished. They have a frayed look. Ends of a pashmina are never braided – that is a sure sign of a fake.

There should be no shine

The fibre produced is a 100% animal product and should have no sheen or extreme shine. Embroidery work may have a shine, and this is usually indicative of silk thread which is more valuable than cotton thread.

The burn test

Pashmina is made from goat hair and should smell like burnt hair if burnt. No, don’t set the pashmina on fire! Gently pull out a thread from one of the unfinished ends. You can also pull out one of the fine hairs sticking out of the fabric (another sign of a real pashmina) and burn it. If it smells like burnt hair and gently dissolves to a fine ash it is probably pashmina.

Pashmina is expensive

If you are being offered a pashmina for less than US$100 it is not real. A completely plain scarf (no embroidery) can cost US$170 at wholesale prices. The more embroidery, the higher the price. Shawls are larger and more expensive than scarves. Some shawls cost well over US$1,000.

Ultimately though, it’s extremely difficult to spot a shawl infiltrated with synthetic and acid-washed. Such a shawl may pass all the tests above. The only test it’ll fail is the test of time.

Join us on a fascinating pasture to loom journey high in the Himalayas on the trail of Pashmina. April 2024.

Sources

Textile Value Chain Textiles of Kashmir, published March 2020

Everything you want to know about pashmina by Pashmoda, published Nov 2021

Signature cashmere The history of Pashmina

Cashmere and pashmina – which country has the best? Pashmina.com

How to buy a real pashmina Suzanne Hooker, Aug 2023

Thanks for taking a look! I am Shila Desai, owner of E.Y.H.O. Tours. I personally handcraft itineraries, infusing them with curated activities, accommodations, and sightseeing. Together with my in-country teams, we deliver exceptional holidays every time. I invite you to leave me a comment or write shila@eyhotours.com

Excellent guide for planning trips! For thrill-seekers, Sage Holidays has the best Ladakh adventure tour.